My curiosity in Marathi movies was aroused, if I remember, in 2004, the year Shwaas released. (It’s among the best Marathi movies, and one that sparked a revival of sorts for Marathi cinema). Although my band of friends as a child consisted of mostly Maharashtrians, and could speak and understand Marathi perfectly, I was more attracted to Hindi- and English-language films back then, not because they were of a better quality, but for an obvious lack of choice. Nothing about Marathi-language films appealed to me. I thought them loud and over-the-top, a combination that never did work for me.

Sometimes I’d watch Marathi plays; but Marathi movies, no. The only Marathi-language films I had watched by the time I turned 10 were V. Shantaram’s Kunku and Dharmatma. My grandfather greatly admired them, and he insisted I watch them with him. Their penetrating themes escaped me, but their craft was exemplary. That’s about as far as I went.

Then came Shwaas. Suddenly, my friends were talking about it. Everybody seemed to be talking about it. It was so popular among the people I knew, who made up my world back then, that I was curious. Its word-of-mouth was particularly strong, and it was a time when a film’s word-of-mouth was a more reliable factor in deciding if a film was worth watching. It was a time when film reviews languished somewhere inside the pages of the newspapers. I did not know what the critics thought of the film but I made up my mind to watch it.

I didn’t watch it until seven years later.

A Seminal Work of Art

To say Shwaas is a seminal work of Marathi cinema is not an exaggeration. It’s a profoundly moving film, modest and straightforward, a rarity these days, and it was a rarity back then, too.

I write about Shwaas because it is the film that irreversibly changed the way I regarded Marathi cinema. If it weren’t for that film, I would still be thinking poorly of it and the kind of talent it nurtures. Growing up in Mumbai, for a Marathi movie to evoke the kind of response it did was as astonishing a feat as any. It shook my world, and I am glad that it did.

I now find that every year there is at least one Marathi-language film that reminds me how wrong I was about Marathi cinema as a kid. Among the latest Marathi movies, it was Aadish Keluskar’s daring and elusive Kaul in 2016, Avinash Arun’s magnificent Killa, a year prior to it and very recently Lapachhapi.

And yet it remains largely inaccessible to audiences outside Maharashtra for several reasons. I will only be tackling one in this piece: “Where to begin?” What are the essential Marathi-language films that a novice needs to watch? It’s a tricky question, for there cannot be any such definitive list. I can only recommend the films that are personal favourites of mine, films that I have seen and marveled at time and time again. In the process I will also try to address a more pressing question: “What makes them great?”

These films must not be incorrectly tagged as the ‘greatest Marathi-language films,’ for that is subjective. [Related: 107 Years Of Indian Cinema: 100 Iconic Films]

1. Samna (1974)

Director: Dr. Jabbar Patel

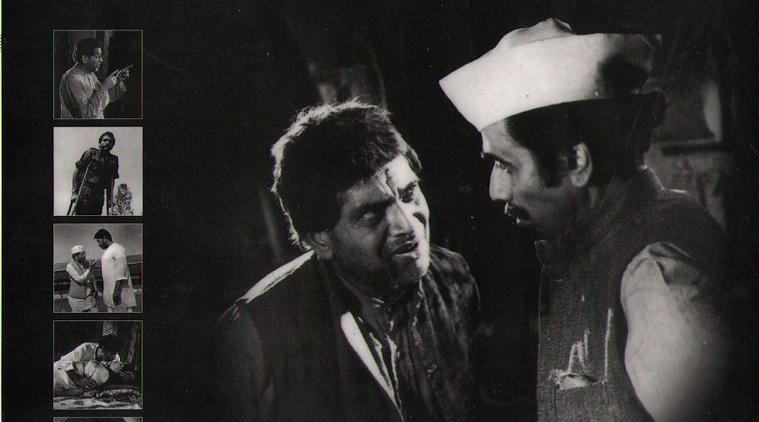

Dr. Jabbar Patel’s entire filmography (especially Umbartha) deserves a place on this list, but this is the first of the two films of his that I will include. Samna, made in 1974 from a script by the great playwright Vijay Tendulkar, has not aged as well as one would have thought, but its message is still pertinent. Samna (“Confrontation”) is a duel of wits between an egotistical and crafty sugar baron and a former teacher, now the local drunk. The sugar baron is rich and successful, feared by his people, and the drunk uncovers dark secrets of his, while under his hospitality. With nothing but the truth on his side, the idealistic Master (as the baron addresses him), accosts the queasy but influential sugar baron to own up.

The sharp writing, typical of Tendulkar, is what first caught my attention. The exchanges between the two are staged with deftness and performed to perfection. Master often counters the sugar baron’s boastful remarks with an incisive question, but it’s not a film where they bicker throughout. Tendulkar develops their relationship carefully. They are neither friends nor brothers; they respect each other, fear each other, but also trust and listen to each other. Violence is spoken of, not shown. Angers simmer, but neither of the two expresses it. A lesser screenwriter, and indeed a lesser filmmaker, would have settled for something more generic, but Tendulkar and Patel, along with two greats of Marathi cinema, Shriram Lagoo and Nilu Phule, pull off something astonishing.

(Here’s an excellent piece by Scroll on why Jabbar Patel’s Samna is a landmark film)

2. Sinhasan (1979)

Director: Dr. Jabbar Patel

Making a political film in India is a delicate task. The filmmaker who undertakes it needs to show tact and pluck. The film may very well find itself embroiled in a controversy once released, or maybe even before it does. The filmmaker, therefore, must make a ‘safe’ political film, as if such a thing exists, or prepare to fight it out with political groups till one party buckles.

Sinhasan (“Throne”), based on Arun Sadhu’s novel of the same name and adapted for the screen by Vijay Tendulkar, walks that tightrope between safe and controversial. It was made, I suppose, in a far more tolerant environment, because it comes away with making broad accusations, unmasking the nexus between politicians and the country’s businessmen, but does it ever so shrewdly. It’s an ambitious film, intricately plotted and absorbing, and impressively enough, eschews the preachiness that inevitably shows up in many Indian political dramas. In the end, Sinhasan leaves us neither shaken nor shocked, and I do not think that was the makers’ intention, but it leaves us with a lot of food for thought.

3. Kunku (1937)

Director: V. Shantaram

My most vivid memory of Kunku (released as Duniya Na Mane in Hindi), a film comprising of many remarkable moments, is the scene in which the bride sees her to-be husband for the first time. They are about to exchange garlands, and, just before placing it around his neck, she is shocked to discover that she is being married off to a much older widower. When they came to her house with the proposal, the old man was accompanied by his young son. And when she peeked through the window to catch a glimpse, she assumed she would be getting married to the younger man. Her apparent horror is followed by sudden reluctance. Her foster father, aware of this deception, hurries forward and forces her to go through with it.

Kunku was a film way ahead of its time. It openly condemned the practice of child marriage and the oppression of women. It featured a female character who, instead of just accepting her fate, rebels against her husband, her mother-in-law and her foster parents, and adamantly refuses to adjust to her new life. Shantaram intelligently uses little details to convey what his characters are going through. Although the performances in Kunku are theatrical, one must applaud a film made in 1937, for being more progressive than most films we see today.

4. Shyamchi Aai (1953)

Director: P.K. Atre

It’s a story every child born into a Maharashtrian family listens to, growing up. Sane Guriji’s autobiographical novel Shyamchi Aai (“Shyam’s Mother”), about a mother’s unconditional love for her son and the sacrifices she makes, is a classic of Marathi literature, and was adapted into a feature film in 1953. I haven’t read the book so I cannot comment on whether the film is a faithful adaptation of it. But, having heard snippets of the story from my mother, the characters that I saw come alive on the screen when I first watched it were exactly as I had imagined them. That was good enough for me.

Time might have dampened the charm of Shyamchi Aai, and many may likely find it a slog to sit through. But it has the kind of sincerity and simplicity missing in our films today.

5. Shwaas (2004)

Director: Sandeep Sawant

It’s hard not to be moved by Shwaas (“Breath”). It’s extremely well written and acted, a passionate film made by passionate people, with miniscule budget. And with the limited resources at their disposal, they created something quite remarkable. It tells the story of a young boy who is diagnosed with retinoblastoma, a rare type of malignant cancer affecting the retina of young children. And the emotional turmoil his grandfather goes through when he discovers that the only way to save him is an operation that would leave him blind.

For me Shwaas worked, despite its overly sentimental tone that some people found irksome. We see how people who come from poverty are wary of modern medicine, quite evident in the scene in which the boy’s grandfather hesitates to sign the form that says that if anything goes wrong the hospital shall not be held responsible. Having run into such people during my trips to clinics since I was a child, I could for the first time understand their concerns, when there was a time I used to find their wariness quite amusing. And this is the reason why I felt Shwaas wasn’t too overdone; Sawant simply understood and empathized with his characters. A filmmaker who has great empathy for his characters can never make a bad film. Shwaas is proof of it.

Disclaimer: The article may not be reproduced or distributed, in whole or in part, without prior permission of Flickside.

4 thoughts on “Beginner’s Guide To Marathi Movies: 5 Time-Honored Classics”

Comments are closed.