Portuguese national cinema might not have developed a specific style in the early silent era to draw the attention of international audiences. But that has changed in recent years with Portuguese filmmakers like Pedro Costa, João Pedro Rodrigues and Miguel Gomes. Cinema has been present in Portugal right from the end of the 19th century. The first scripted Portuguese film was made in the year 1907. Starting from 1933, inspired by the conservative ideas of the country’s dictator Salazar, a new Portuguese National Cinema originated. In fact, the 1930s and early 1940s were known as the ‘Golden Age of Portugal Cinema’.

The greatest Portuguese filmmaker Manoel de Oliveira made his first feature film Aniki-Bobo in 1942 and brought in a realistic style that predates Italian Neo-Realism. In the early 1960s, inspired by the French New Wave, a new wave of cinema took the country by storm. But it was only after the 1974 Carnation Revolution – which overthrew the fascist dictatorship – that Portuguese filmmakers were bestowed with liberties. Manoel de Oliveira, the oldest active filmmaker ever, continued making cinema till his death in 2015 at the age of 107. And from the 1990s, Portuguese cinema won several awards in the European Film Festival circuits.

Furthermore, after the revolution, Portuguese cinema transformed itself into a strong dissident voice, capturing the nation’s political, social, and economic conflicts. Without further ado, here’s a look at some of the best and most important Portuguese films of all time:

Best Portuguese Movies, Ranked

25. April Captains (2000)

April Captains marks the directorial debut of multi-talented actress Maria de Medeiros (Pulp Fiction, Henry & June). She boldly chooses the subject of the 1974 Portuguese revolution and a pivotal event that led to the dismantling of the country’s four decade dictatorship. Set on April 24, 1974, April Captains unfolds from the perspective of two military officers who were part of the bloodless coup. Maria herself plays the role of Antonia, a university teacher and a member of the underground resistance movement.

April Captains tells a very simple historical tale with abundant charm and warmth. It’s a story of tyranny brought down by the resilience and determination of the masses.

24. The Strange Case of Angelica (2010)

Writer/director Manoel de Oliveira kept surprising us with his sober formalism even after turning 100. The Strange Case of Angelica – Oliveira’s penultimate feature-film – is a captivating romantic drama with a great visual and narrative sensitivity. It’s set in the river town of Porto and revolves around young Isaac (Ricardo Trepa), a freelance photographer who stays at a modest boarding house. Isaac is asked to photograph the recently deceased Angelica, a beautiful young woman from a wealthy family. Isaac is surprised when he looks at Angelica through his camera’s viewfinder.

The film is a peculiar and funny meditation on the essence of photography and cinema. Eventually, it remains a marvel because of the youthful perspective of its 101-year old filmmaker. Oliveira for the first time is said to have used CGI for a dream sequence in Angelica. And in a way this makes Oliveira — who entered into the film industry in the silent era — as old as the cinema itself.

23. A Song of Lisbon (1933)

Jose Angelo Cottinelli Telmo’s comedy was the first Portugal talkie to be entirely made in Portugal. Mr. Telmo was a multifaceted figure who mastered several artistic disciplines including architecture, cinema, and music. A Song of Lisbon is a brilliant triumph which ushered in a Golden era for Portuguese cinema. It revolves around a slacker medical student Vasco (Santana) who relies on his old rich aunts to fund his hedonistic pursuits. But fate has something else in store as Vasco is soon left with no money and home.

The film opens with beautiful and powerful imagery of Lisbon that reminds us of Berlin, A Symphony of Metropolis (1927). The comedic aspects are sweetly ridiculous and largely entertaining.

22. The Mutants (1998)

Actor and director Tessa Villaverde’s third directorial venture was a bleak drama about Lisbon’s homeless youths abandoned by the juvenile system. It revolves around three central teenage characters: Andreia, Pedro, and Ricardo. Forced to become adults, the teenagers navigate their way through the dog-eat-dog world. The film marks the acting debut of well-known Portuguese actress Ana Moreira’s (Tabu). Her intoxicating performance as Andreia drives the narrative.

Tessa Villaverde realises the life of the teenagers with great authenticity and grit. Besides, she never lets the narrative turn into misery porn. The Mutants was screened at the Un Certain Regard section in Cannes. The film sparked a nation-wide debate on the reform of homeless youths.

21. No, Or the Vain Glory of Command (1990)

Manoel de Oliveira’s deeply philosophical anti-war drama is set in the Portuguese African colony of Angola in the year 1973. The narrative unfolds as a series of conversations between a drafted history scholar soldier and the various members of his brigade. They are on their way to control a rebel insurrection in the so-called overseas provinces. The conversations among the soldiers revolve around Portuguese military history, its watershed moments, decisive battles, and many failures.

From 2nd century B.C. to the modern colonial history of Portugal, Oliveira contemplates the numerous tragedies that were part of Portuguese’s empire building ambitions. It’s a powerful history lesson which focuses on the human cost of wars.

20. Alice (2005)

Marco Martins’ claustrophobic drama follows a father obsessively searching for his missing daughter. Nuno Lopes offers a fantastic performance as the father, Mario. He develops an unusual video surveillance network to find any clue regarding his little daughter’s disappearance. The initial premise of Alice might sound like it belongs to the thriller genre. But director Marco turns it into a haunting character study. It’s also a heartbreaking portrait of grief, loss, and obsession.

Marco Martins permeates the imagery with a blue colour palette, reflecting the father’s grief and anguish-ridden perspective. The film ends on a deeply uncomfortable note, and it can be emotionally overwhelming on the whole. Alice won a special prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

19. The Ornithologist (2016)

Joao Pedro Rodrigues’ films possess the freewheeling spirit of the auteurs Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Miguel Gomes.In this absurdist queer drama, Rodrigues tells the tale of a gay ornithologist’s misadventures in the picturesque wilderness of Northern Portugal. The ornithologist Fernando is in search of an endangered species. His canoe gets stuck in the rapids, but he is miraculously saved by Chinese tourists. But Fernando encounters more sinister obstacles.

The film travels into stranger territory in the second-half as Rodrigues juxtaposes beautiful images of nature with his madcap imagination. Nothing much makes sense in the ornithologist’s journey. But it’s a dazzling sensory experience that eventually reflects on spirituality.

18. Blood of My Blood (2011)

João Canijo worked as an assistant director to Manoel de Oliveira and Wim Wenders. He made his debut feature Three Less Me in 1998, and his films have often won several international film festival awards. Blood of My Blood is Canijo’s most epic and affecting work which delves into the everyday life of a Lisbon working class family. The family’s matriarch Marcia single-handedly raises her two children while working in a restaurant.

Canijo prepared for this film in a unique manner. Like British director Mike Leigh, he developed the characters with the actors through a series of workshops. And that particularly shows in the spellbinding performance of Rita Blanco in the central role of Marcia.

17. The Courtyard of the Ballads (1942)

Francisco Ribeiro’s Courtyard of the Ballads is set in a Lisbon neighbourhood and captures the dreams and passions of different individuals. The narrative unfolds during the annual celebration of St. John the Baptist’s holiday. The film offers a criticism of the urban environment and at the same time champions the traditional values and people’s solidarity. Though Ribeiro’s film conforms to the authoritarian rule’s basic ideology, its setting and characters are considerably nuanced compared to other Portuguese national cinema of the time.

The film presents a conservative view of modern society with ample emotional scenes and memorable comedic moments. It may lack the strong critique found in William Wyler and Frank Capra’s movies. But it’s as entertaining and engaging as the American masters’ cinema.

16. O Sangue (1989)

Portuguese auteur Pedro Costa uses his dreamlike aesthetics to highlight the sufferings of his nation’s marginalised underclass. He is best known for his fiction and documentary hybrids. O Sangue (‘The Blood’) was his directorial debut and possesses most of his thematic preoccupations including social maladjustment, unresolved trauma and displacement.

The wafer-thin plot revolves around a young man who tries to protect his little brother after the death of their father. O Sangue unfolds like a tragic fable and is strengthened by its breathtaking cinematography. There’s a sense of magic and wonder that saturates every frame. Costa’s ability to extract lyricism and beauty out of mundane and dilapidated settings is unparalleled.

15. Our Beloved Month of August (2008)

Film critic-turned-filmmaker Miguel Gomes’ second directorial venture was a freewheeling documentary-fiction hybrid. This quirky and charming film is set in the rural mountain region of Aragnil. It initially unfolds like a documentary travelogue that’s full of panoramic landscapes and provincial charm. Gradually, the narrative shifts gears as it revolves around a teenage singer named Tania and her domineering father, Domingos.

However, there’s more to the film than familial conflicts and forbidden love. In fact, Our Beloved Month of August is a narrative of multitudes and looks at the self-reflexive nature of cinema. It’s the first of the many refreshingly creative and uncategorizable movies that populate Miguel Gomes’ oeuvre.

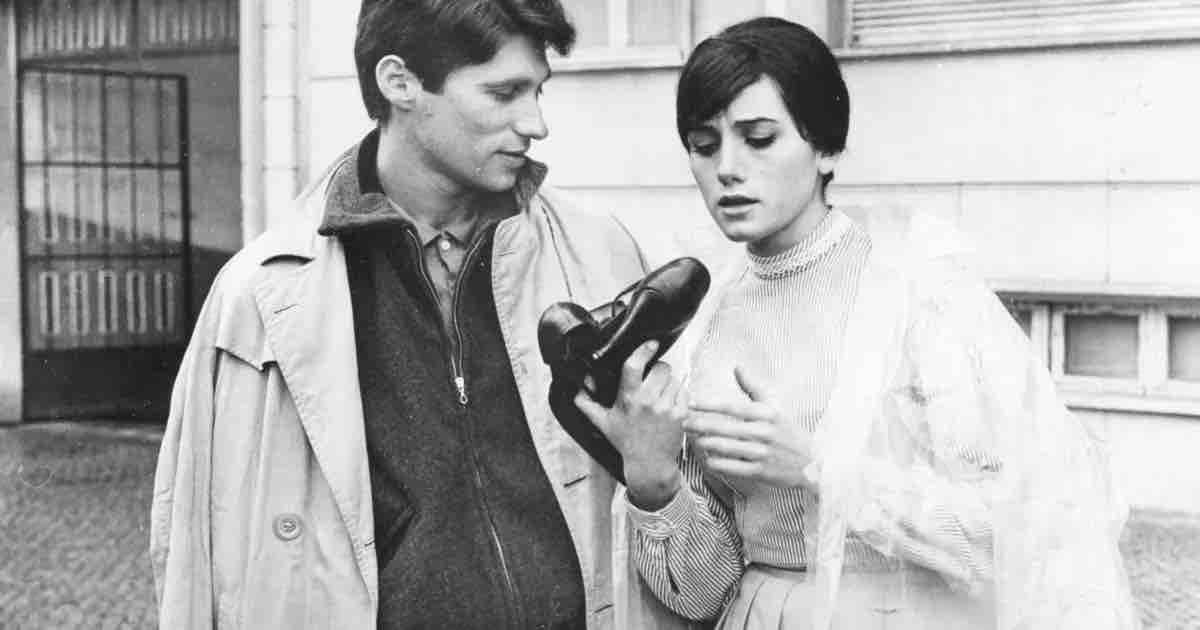

14. The Tyrant Father (1941)

Oliveira Salazar was the Portuguese dictator who came to power in 1932. He distanced himself from Italian fascism and Nazism that was on the rise, and promoted his regime as nationalist, capitalist, and conservative. He called his regime as Estado Novo (New State) and of course like any authoritarian rule, Salazar used secret police and censorship to uproot opposition. Although film production was not directly controlled by the state, Estado Novo saw cinema as a medium for propaganda. However, there were few works that didn’t carry the regime’s official ideology. One such film was Tyrant Father, a popular comedy directed by António Lopes Ribeiro.

The narrative revolves around amateur theatre performer and shoe-seller Francisco who falls in love with a perfume-seller and cinema buff Tatao. This leads to a hilarious showdown between theatre and film, and between different social classes. Overall, it’s a sweet and whimsical farce that reminds us of the best Ernst Lubitsch movies.

13. Francisca (1981)

Francisca is the last film in Manoel de Oliveira’s ‘Tetralogy of Frustrated Love’. All the four sprawling literary adaptations are known for their long-takes and tableau-like mise en scène. Moreover, the narratives focus on the ruthless social circles of aristocrats. Francisca, based on Agustina Bessa-Luis’ 1979 novel Fanny Owen, is a retelling of the real and troubled 19th century romantic rivalry between acclaimed author Camilo Castelo Branco and his friend Jose Augusto. They compete for the affection of Francisca Owen (Teresa Menezes), the daughter of an English officer.

The film is a brilliant portrait of obsessive love. Oliveira’s museum painting-like atmosphere and deadpan humour may not work for all. Similar to Kubrick’s monumental classic Barry London (1975), Oliveira looks at his characters with a detached amusement.

12. The Green Years (1963)

Director Paulo Rocha’s Green Years is a magnificent time capsule of early 1960s Lisbon. It revolves around 19-year old Julio (Rui Gomes) coming to Lisbon from a provincial town to make a living in the big city. He stays with his uncle and falls in love with the young, free-spirited maid Isabel living nearby. Soon, he contemplates the disparities and lack of opportunities in the rapidly urbanising city.

Green Years is a significant film among the short-lived Portuguese New Wave, especially for utilising the space and architecture to narrate the story. It reminds us of Michelangelo Antonioni’s portrayal of loneliness and alienation through urban spaces. Paula Rocha served as an assistant to the great Manoel de Oliveira and French master-filmmaker Jean Renoir.

11. Recollections of the Yellow House (1989)

João César Monteiro is known for his quirky Portuguese dramas. The ‘trilogy of João de Deus’ is his most acclaimed work. The first instalment of this trilogy was Recollections of the Yellow House. The trilogy revolves around João de Deus, an intelligent yet depraved middle-aged scoundrel who is perceived as the filmmaker’s alter-ego. Monteiro himself plays the central character. He inhabits a simple room in a yellow boarding house. João spends his time lusting after Julieta, a young woman and the daughter of his landlord Violeta.

Monteiro offers an unconventional portrait of a solitary middle-aged urban man. Yellow House is also a caustic satire that questions one’s idea of insanity, age, desire, and beauty.

10. God’s Comedy (1995)

João César Monteiro’s provocative comedy and second instalment in the trilogy of João de Deus once again defies easy categorization. In this film, the perverted and intelligent man is left with the task to oversee an ice-cream shop. Soon, João’s lustful nature becomes apparent as he is infatuated with a country girl and a butcher’s daughter.

In God’s Comedy, Monteiro explores his idiosyncratic character in a more interesting and lucid manner. He once again satirises the confines of Christian morals and conservatism. Nothing is sacred and nothing escapes the sardonic perception of Monteiro. From a visual and writing standpoint, Monteiro strongly builds on the style he created in Recollections of Yellow House.

9. Abraham’s Valley (1993)

From the 1978 film Doomed Love, Manoel de Oliveira’s filmmaking style is said to have undergone a change. His fondness for aristocratic settings and exploration of profound philosophical themes brought a certain distinct quality to his works. Oliveira himself was born into privilege. Doomed Love and Satin Slipper (1985) are some of Oliveira’s prominent literary adaptations that are also known for their epic run time (4+ hours). Unfortunately, these films are largely unavailable. Abraham’s Valley, his 13th feature-film, also offers a haunting portrait of the aristocrat class.

Based on a novel by Agustina Bessa-Luis, the film elegantly realises the melancholic life of Ema (Cécile Sanz de Alba), stuck in a loveless marriage with a wealthy older man. The static camera compositions and the novelistic way of storytelling add depth to Ema’s existential crisis.

8. Letters from Fontainhas Trilogy

Shot over the course of a decade, Pedro Costa’s loose trilogy known as ‘Letters from Fontainhas’ consists of Bones (1997), In Vanda’s Room (2000), and Colossal Youth (2006). Fontainhas is a slum community situated in the outskirts of Lisbon. It’s largely populated by immigrants from Cape Verde.

Blending fiction and documentary, Costa looked at the lives of its inhabitants, chronicling the danger, death, and decay surrounding them.

With this trilogy, Pedro Costa totally eschews conventional storytelling and brings a vision of poverty that’s fascinatingly aestheticized. Casting local residents to play a version of themselves, Costa observes the day-to-day anguish of being caught in the lower depths of society.

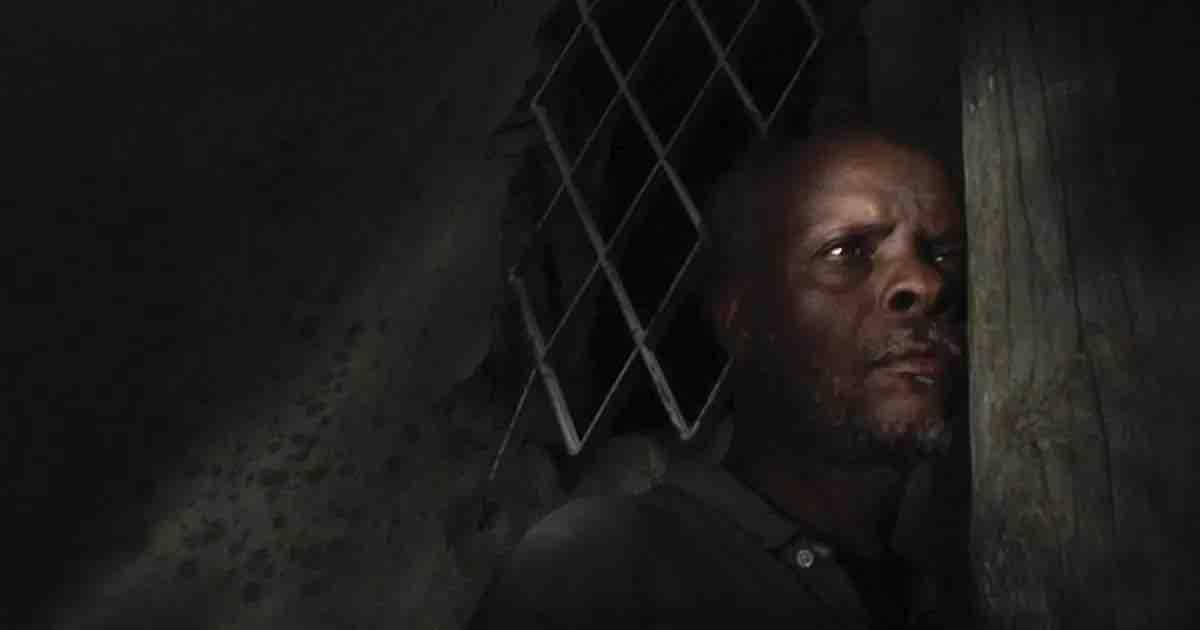

7. Vitalina Varela (2019)

Portuguese auteur Pedro Costa has been focusing on the plight of Cape Verdean immigrants ever since he made Casa de Lava in 1994. In Vitalina Varela, the focus of interest is Vitalina, who played a supporting role in Costa’s Colossal Youth and Horse Money. Similar to Costa’s previous features, it blurs the line between fiction and documentary as Vitalina plays herself. She re-enacts her journey to Lisbon after the death of her husband there.

Though the feelings of grief are drawn from Vitalina’s real life, Costa intertwines interesting visual juxtapositions to enhance his purgatorial vision of Lisbon’s impoverished quarters. Vitalina co-wrote the script with Costa. Furthermore, Costa’s regular Ventura makes his presence as a priest.

6. Aniki-Bobo (1942)

Manoel de Oliveira is the most celebrated Portuguese filmmaker, and also known as the world’s oldest filmmaker. His first cinema project was in 1927, at the age of 19. He was making films till his death in 2015. This is how the Senses of Cinema article introduces him: “he had been a director for 88 years, longer than most of us manage simply to stay alive.” Aniki-Bobo was Oliveira’s first feature-film which is set in the director’s hometown Porto.

Acknowledged as the predecessor to Italian Neo-Realism, the film follows a rivalry between groups of poor school-age children. Shot in a real working-class environment, Oliveira used the child characters to make subtle criticisms of the authority. The film, however, failed commercially and Oliveira stayed away from filmmaking for the next fourteen years.

5. The Metamorphosis of Birds (2020)

Catarina Vasconcelos’ Metamorphosis of Birds is a poetic memoir, retracing the lives and times of Vasconcelos’ family. It begins with the love story between Catarina’s paternal grandparents. The grandfather Henrique is a Portuguese naval officer geographically separated from his immediate family. There’s grief and loss in this account of the past alongside beauty and love. Debutant filmmaker Catarina doesn’t treat the material as a straightforward documentary. It’s more like an evocative film essay with bits of fictionalised dramatic sequences.

Catarina’s visual storytelling abilities are spellbinding. She and her cinematographer Paulo Menezes create painterly-images that deftly express the individuals’ yearning and inner beauty. The film is eventually an ode to motherhood and the eternal cycle of life and death.

4. Horse Money (2014)

Horse Money is Pedro Costa’s yet another deeply melancholic and multi-layered drama, which unlike his other films offers a commentary on Portuguese history. The film revolves around the painful memories and existence of Ventura – an immigrant from Cape Verde and the central character of Costa’s Colossal Youth. Ventura, a retired bricklayer, wanders the dimly lit and abandoned hospital corridors reminiscing about the past. In fact, Ventura initially believes that the year is 1975.

Furthermore, he thinks that he was brought to hospital by the revolutionary army during the Carnation Revolution of 1974-1975 when the nation’s authoritarian government was overthrown.

Horse Money is a visually stunning journey through the fragmented memories of Ventura. The man haunts the dilapidated space like a ghost as if he is caught in a limbo and left to process his internal malaise.

3. Tabu (2012)

Shot in grainy black-and-white, Miguel Gomes’ internationally acclaimed feature was a poetic meditation on memory, love, and isolation. One of the finest films of the 2010 decade, it pays homage to the title and structure of F.W. Murnau’s last silent film, Tabu: A Story of the South Seas (1931). Tabu’s bipartite structure at first revolves around a devout elderly woman named Pilar and her grumpy and senile neighbour Aurora. In the second-half, a stranger who comes to meet Aurora in her death bed recalls his love affair with her in an unnamed African country.

Though Tabu seems like a familiar romantic tragedy, it also doubles up as a fascinating examination of colonial history. Besides, it profoundly explores the contrasts between love and loneliness, youth and old age.

2. The Arabian Nights Trilogy

Miguel Gomes keeps challenging our preconceptions about his abilities as a filmmaker. It greatly prevails in his sprawling three-part, six-hour epic that’s very loosely inspired by One Thousand and One Nights. Miguel’s masterwork eschews traditional cinematic narrative structure and utilises his series of fable-like segments to deeply examine Portugal’s financial and political crisis. That may sound like a heavy subject but Miguel imbues the anarchic and magical spirit of the source material to create multi-dimensional tales of humanity and social ruin.

The three volumes of Miguel Gomes’ Arabian Nights are made up of separate small stories, and material for these stories largely came from real life. The filmmaker actually brought together a team of journalists to come up with these strange yet true stories.

1. Mysteries of Lisbon (2010)

Prolific Chilean filmmaker Raul Ruiz’s last film was based on the 1854 novel of the same name by renowned Portuguese author Camilo Castelo Branco. At a runtime of 4.5 hours, its complex narrative, full of tales within tales, follows an orphan named Pedro da Silva and the search for his origins. The ensuing story, dealt with skill and precision, takes us to contrasting landscapes of Portugal, Brazil, France, and Italy.

Similar to the works of Manoel de Oliveira, Raul stages the vignettes in a painterly manner. He brilliantly engages with Branco’s dense source material. Carlos Saboga’s script gracefully guides us into the many subplots of this sweeping tale without ever confusing us. Overall, this is a sprawling existential story made under the guise of a lavish period drama.

Conclusion

There we are! These are some of the best Portuguese movies of all time. Starting from the 1980s, a new breed of film artists have expanded the scope of Portugal’s small film industry. Most of these filmmakers were cinephiles, who learnt cinema in an academic environment. These artists continue to engage in narrative experiments that comment on Portuguese social and political reality. The Lion of the Star (1947), Change One’s Life (1966), Hovering Over the Water (1986), Down to Earth (1994) Jaime (1999), Jose and Pilar (2010), Ashore (2018), and Around the World When You Were My Age (2018) are some other feature films and straightforward documentaries worth checking out.

What are your favourite works of Portuguese cinema? What did we miss? Tell us in the comments below.