From Harakiri (1962) to Seven Samurai (1954), these are the best Samurai movies of all time.

Samurai movies have much in common with the Western Hollywood genre. The cinematic persona of samurai and cowboys have been both real and mythic. In fact, mythology overrides reality often, and these heroic figures are ordained to become the symbol of an idealised past. Gunplay and swordplay sure fascinated early movie-goers. But over the years, samurai films – like their Western counterparts – have gone through several changes in terms of style, themes, and storytelling method. From Akira Kurosawa, Masaki Kobayashi to Takashi Miike, Japanese filmmakers have offered their own unique take on the chanbara (sword fighting) and jidai-geki (period drama) genre, to which the samurai cinema belongs.

Samurai are believed to have existed since 7th century Japan. However, the samurai era began late 12th century onwards.They were the officer caste and military nobility of Japan from the medieval era to the early-modern era, i.e., from 1185-1868. The samurai way of life was formally defined by the Bushido Code, a set of moral and ethical values. However, like any codes, Bushido was interpreted in different ways in different eras, and largely existed to serve the aristocracy. During the peaceful Edo Period (1603-1868) when power was de-centralized from emperor to a group of daimyo (regional lords), samurai’s well-being depended on their allegiance to the daimyo. And most often lord’s wishes could be against the bushido code of samurai.

Such conflicts between power and ethics, honour and greed became fascinating ingredients for samurai cinema. As a matter of fact, many samurai movies were set during the Edo or Tokugawa period. The 1950s and 60s marked the golden age of samurai cinema. Similar to the Western genre, the jidaigeki genre gradually lost its prominence in the late 20th and early 21st century. Yet, quite a few revisionist works are being made, which allow us to perceive such allegedly heroic figures under a new light.

Quickly then, here are some of the best Samurai movies that should be on your watchlist.

Best Samurai Movies, Ranked

20. After the Rain (1999)

Takashi Koizumi’s directorial debut was based on a screenplay written by the late Akira Kurosawa, who passed away in September 1998. Koizumi worked as the first AD for Kurosawa from the master’s 1980 epic Kagemusha. Surprisingly, After the Rain is a warm-hearted and low-key drama unlike any of Kurosawa’s grand samurai classics. Musician-turned-actor Akira Terao plays the gentle and polite wandering ronin, Ihei Misawa. Accompanying him in his journeys was his beloved wife, Tayo.

Ihei and Tayo stay at an inn when heavy floods make it impossible to cross the river. Ihei does his best to help the poor and gentle-spirited folks stranded at the inn. A skilled sword master, Ihei’s heroics reach the attention of a local lord. Comparisons are inevitable, but Koizumi does a fantastic job crafting this subdued tale of an ideal and altruistic samurai. His precise staging and striking scenery are frankly a wonder to behold.

19. Chushingura (1962)

The tale of 47 Ronin is one of the most famous events in Japanese history. At the beginning of the 18th century, a band of ronin vowed to avenge the death of their daimyo (regional lord) who was compelled to perform hara-kiri (ritual suicide). A powerful Shogunate official was considered responsible for the lord’s death. Hence, the ronin made an elaborate plan to assassinate him. This story was well-known even during the Tokugawa era and inspired many kabuki and bunraku plays. Several movie versions of 47 Ronin were made. The earliest surviving one was Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1941 adaptation.

Hiroshi Inagaki rendered the tale of 47 ronin in Chushingura on a monumental scale. It’s probably the longest samurai film after Seven Samurai (runs 207 minutes). Inagaki’s unfussy storytelling and impactful characterizations keep us thoroughly invested. Mifune plays a cameo and Chushingura happens to be Setsuko Hara’s final film as she announced retirement in 1963.

18. Zatoichi: The Blind Swordsman (2003)

With Zatoichi, multifaceted artist Takeshi Kitano has modernized the well-known warrior figure of the 1960s for the 21st century. The writer/director himself plays the titular character, a blind and wandering masseur with a penchant for gambling. Zatoichi is also blessed with exceptional sword-wielding skills, which he hides inside his cane stick. Set during the late Edo period (1830s or 1840s), the film opens with Zatoichi visiting a town under the control of the ruthless Ginzoclan. Meanwhile, a skilled ronin named Hattori (Tadanobu Asano) arrives in town, seeking a job in order to provide for his ailing wife.

The men’s fates cross as they stand against each other in the ensuing conflict. To his credit, Kitano doesn’t direct the film like a regular samurai action drama. The pace is relaxed with fascinating subplots and intriguing supporting characters. The action is quick and brutal. Kitano and his team astoundingly visualize the Edo period Japan. And the soundtrack adds to the exhilarating film experience.

17. Gate of Hell (1953)

The Palme d’Or award-winning Gate of Hell by Teinosuke Kinugasa (Page of Madness) was the first Japanese color film to be released internationally. Set in 12th-century Japan, the story follows the loyal and determined samurai Morito(Kazuo Hasegawa). While defending the castle from rebel forces, Morito saves a beautiful and blue-blooded young woman named Kesa. When his Lord offers Morito to grant a wish, the samurai asks for Kesa’s hand in marriage.

Kesa is already happily married to a skilled swordsman named Wataru Watanabe. Morito doesn’t take ‘no’ for an answer and that sets off a chain of tragic events. Filmed using Eastman color, Gate of Hell must be seen for its breathtaking visuals and magnificent art direction. It certainly lacks the storytelling complexities of an Akira Kurosawa or a Kobayashi movie. Yet the detailed imagery and the central emotional conflict keep us invested. Gate of Hell won two Academy Awards for Best Costume and Best Foreign Film.

16. Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (1955)

Tomu Uchida is a versatile and stylish genre filmmaker who directed films between 1927 and 1971. This was Uchida’s first post-war Japanese film. After the end of the war in 1945, he went to work for the Japanese-owned Manchuria Film Association and assisted in the technical improvement of Chinese cinema. Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji revolves around a group of travelers on their way to Edo. It chiefly focuses on a young samurai, Sakawa Kojuro, and his two servants, Genpachi, the spearman, and Genta, the comical servant.

The trio encounters minor challenges along the way and the young samurai experiences somewhat of an inward journey. The structure of Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji slightly reminds us of Canterbury Tales. Like Chaucer’s stories, the movie unfolds in an episodic manner with plenty of subplots and characters. Interestingly, the various subplots are finely integrated into the storyline. Overall, the samurai movie works as a morality drama and an examination of the era’s socio-economic condition.

15. The Tale of Zatoichi (1962)

The blind swordsman and masseur Ichi is one of the most popular heroes in Japanese cinema. The character has inspired one of the long-running film series of all time. Between 1962 and 1989, 26 Zatoichi films were made. A Zatoichi TV series was broadcasted from 1974 to 1979, running for close to 100 episodes. Until Takeshi Kitano’s remake of Zatoichi in 2003, all the movie and TV versions of Zatoichi were played by the burly and charming actor Shintaro Katsu. Kenji Misumi’s 1962 film first introduced us to these idiosyncratic movie characters.

Zatoichi first appeared as a minor character in a short story written by novelist Kan Shimozawa in 1948. Therefore, Katsu and director Misumi were responsible for building a solid foundation for this well-known swordsman figure. The 1962 film closely focuses on Ichi’s nature, from his humor, humanity to his mesmerizing blade-wielding skills. The poetic compositions and lush black-and-white cinematography add to the film’s beauty.

14. Sanjuro (1962)

Akira Kurosawa continued the exploration of his anti-hero samurai character Sanjuro (he designed in Yojimbo) in his eponymous 1962 film. The film opens with a group of nine young samurai discussing their course of action to handle a corruption scandal in town. Once the hapless samurai have laid out their plan, they are shocked to find a grizzled samurai in the back of the dark room. The cocky Sanjuro has overheard their plans and is convinced that the young warriors would only be killed in the process. Sanjuro, therefore, devises a hazardous plan that might, despite its risks, benefit the samurai.

While in Yojimbo, Sanjuro remained a smug anti-hero with no morals, in this spiritual sequel Sanjuro operates under some moral code. The script keeps us guessing the reason behind each of Sanjuro’s actions. But Kurosawa’s sleek direction and excellent action choreography are the film’s most alluring features. Sanjuro is clearly the most accessible samurai film for those trying to get into the genre.

13. Lone Wolf and Cub Film Series

Veteran Japanese filmmaker Kenji Misumi’s Lone Wolf and Cub film series is based on the best-selling manga by writer Kazuo Koike and artist Goseki Kojima. The six films in the series, which were made between 1972 and 1974, expanded the scope of chanbara genre movies. The manga series and the movies influenced artists outside Japan including Tarantino and the illustrious comic book author Frank Miller. Set in 18th-century Japan, the story follows a gruff, wandering ronin Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama).

Accompanying Ogami in his journey through the countryside was his infant son, Daigoro. Ogami held a high-ranking position as Shogun’s (Emperor) executioner. When Ogami’s own clan frames him as a traitor and murders his wife, the samurai sets out to seek revenge. Director Misumi strikingly balances tender drama and chaotic, bloody action. The film lays bare the hypocrisies and injustices of the conservative Shogunate era.

12. 13 Assassins (2010)

One of the best modern samurai movies, Takashi Miike’s ultra-violent 13 Assassins is a remake of Eiichi Kudo’s 1963 film of the same name. The scenario is the same, like in Seven Samurai, The Magnificent Seven or 300. Set in 1844, the Japanese film follows the excruciating efforts of a group of honorable samurai undertaking a covert mission to kill the sadistic younger brother of the Shogun (emperor). Led by the charismatic swordfighter Shinzaemon Shimada (Koji Yakusho), the 13 embark on this suicide mission to make sure that the rogue tyrant is dispatched before he gains more power within the Shogunate.

Obviously, 13 Assassins is a film with two contrasting halves. In the first, we are introduced to an array of characters and their motivations. The political maneuvering is particularly fascinating to witness. The later-half is driven by the thrilling and chaotic swordplay. Miike’s supremely entertaining action scenes pay enough homage to the samurai classics. He also uses lots of gallows humor to lighten the grim tone.

11. Kill! (1968)

Kihachi Okamoto’s Kill! is a fun parody, which borrows and combines Spaghetti Western and classic samurai film features. It can be viewed as a companion piece to Sanjuro since the storylines are fairly similar. The story revolves around two unfortunate men, Genta (Tatsuya Nakadai) and Hanjiro. Genta is a ronin, Hanji an ex-farmer. The two show up in a dusty village and work for opposing sides of a dangerous clan. Soon, Genta comes across a group of seven good-hearted wannabe samurai. The group wants to fight against a corrupt, power-hungry chamberlain.

The legendary Nakadai effortlessly plays the Sanjuro-like character without trying to imitate the swagger of Mifune. Kill! has some genuinely exciting action sequences. At the same time, it works as a hilarious parody of the samurai film tropes. The conspiracies become too convoluted at times to follow. Yet the humor and action make it a satisfying and pulpy samurai flick.

10. Three Outlaw Samurai (1964)

Three Outlaw Samurai marks the directorial debut of Hideo Gosha, who made quite a few successful yakuza and samurai action dramas. The story revolves around a wandering ronin named Sakon Shiba (Tetsuro Tamba). He comes across three peasants at an old mill, who hold a young woman captive. The woman is the daughter of a corrupt and cruel magistrate, who has refused to hear the peasants’ pleas. Sakon decides to join the peasants’ cause in exchange for food and shelter.

Soon, the magistrate’s men come to retrieve the daughter and kill the peasants. Interestingly, two warriors who’re part of the magistrate’s band of Ronin change sides and join Sakon. Three Outlaw Samurai gives the feel of Seven Samurai or Yojimbo, although it’s a contained and small story. What’s particularly interesting about the film is that it constantly upends audience expectations. Besides, Gosha critiques the samurai class for being opportunistic tools of their masters.

9. Samurai Assassin (1965)

Kihachi Okamoto’s Samurai Assassin has a complex, multi-layered political narrative at its center. Set in the year 1860, a band of assassins waits outside a snow-covered castle to assassinate the lord of House Ii, a high-ranking official of the Tokugawa Shogunate. The assassins mostly belong to Ii’s rival clan, Mito. When the lord doesn’t show up at the castle’s gates one particular day, the clan fears that there might be a traitor among their group. Suspicion falls on Niiro (legendary Toshiro Mifune), a ronin who desires samurai status, and Kurihara, an aristocrat and a scholar of Western philosophy.

Niiro is one of the darkest characters Mifune’s played in his career. On the surface, Niiro appears to be a roguish yet playful ronin like Sanjuro. Gradually, as we learn his story, we understand how deeply frustrated his character is.

Okomoto brilliantly sets up Niiro’s self-destruction during the bloody, gut-wrenching finale. Samurai Assassin remains a hard-hitting study of the decline of the samurai class.

8. The Twilight Samurai (2002)

Yoji Yamada’s lyrical drama looks at the everyday life of a samurai and his family in mid-19th century Japan — the end of the Tokugawa dynasty. Hiroyuki Sanada plays Seibei Iguchi, a good-hearted and honorable low-ranking samurai, who works as a bureaucrat. Seibei is struggling financially and has lost his wife. He single-handedly raises his two daughters and takes care of his senile mother. Seibei’s life changes when reconnects with his childhood sweetheart Tomoe, who’s divorced her abusive spouse and moved back to town.

Yoji Yamada gracefully deals with modern themes such as single parenthood, and women’s empowerment in the 19th-century setting. What’s more fascinating about Twilight Samurai is the gentle characterization of Seibei. Though he is a master swordsman, there’s a vulnerability to him that makes his character very real and relatable. Yoji Yamada followed Twilight Samurai with two more nuanced samurai dramas, The Hidden Blade (2004) and Love and Honour (2006).

7. The Samurai Trilogy (1954-1956)

Hiroshi Inagaki’s trilogy narrates the fictionalized story of legendary swordsman and philosopher Musashi Miyamoto (1584-1645). Inagaki’s movies were based on Eiji Yoshikawa’s 1930 novel about Miyamoto. In fact, Inagaki already made a film based on the novel in 1942, which was destroyed during the war. The new version stood out for its rich colors and a fiery central performance from Toshiro Mifune. An interesting side note — Mifune worked in more movies with Inagaki (21) than Kurosawa (16).

The story chronicles Musashi Miyamoto’s life journey from a bewildered youth to a confident samurai master. The trilogy was a testament to Inagaki’s storytelling abilities. In his four decades as a filmmaker, from the silent age of film to 1970, he gave us several classics.

There are times when the lyrical dialogues, melodrama, and romantic subplots get too intense. Yet Inagaki effectively mixes dramatic portions with startling action set-pieces. Mariko Okada turns in a captivating performance as the destitute Miyamoto’s lover, Akemi.

6. Throne of Blood (1957)

Akira Kurosawa’s 16th-century samurai film offers one of the most fascinating interpretations of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. The film might annoy Shakespeare purists as Kurosawa eschews Bard’s words. Moreover, he made his actors perform in Noh style, a classical Japanese performance art that’s popular among the upper class. Noh theatre employs masks as signifiers and focuses on an austere style with minimal props and music. Most importantly, Akira Kurosawa omitted a lot of elements from the play.

The film wasn’t a commercial disaster but also didn’t bring much profit to the studios. However, in the ensuing decades, Kurosawa’s experiment with style and imagery was widely acclaimed. His austere yet stunning landscape imagery – crafted in the style of Noh stage – provides a strong cinematic sensibility to the narrative. The spider web forest scene and the final death scene speak of the master’s ability to create mesmerizing visuals. Mifune’s raw, animalistic performance is, as usual, exceptional.

5. The Sword of Doom (1966)

Samurai cinema of the 1960s repeatedly explored the abuse of bushido code by the ruling as well as the warrior class. These were entirely different from earlier era’s depiction of samurai as the sole heroic figure. In fact, Japanese filmmakers used the jidaigeki (period drama) genre to condemn militarists and reflect the turbulent political landscape of 1960s Japan. But no samurai film comes close to cynicism and nihilism as Kihachi Okamoto’s Sword of Doom. Based on the novel by Kaizan Nakazato, the story is set during 1860s Japan when the Shogunate era came to an end.

Sword of Doom’s protagonist or anti-hero is Ryonosuke (Sword of Doom), a disgraced samurai whose lust for violence leads him down the path of self-destruction. He is a sociopath who kills people for no reason. Fans of the chanbara (sword-fighting) genre are rewarded with three outstanding fight sequences. One of the best samurai movies ever made, Sword of Doom is also a haunting character study of an evil mind.

4. Yojimbo (1961)

Yojimbo was one of the most commercially successful films in Kurosawa’s directorial career. Set in the year 1860, at the end of Tokugawa Shogunate, a ronin named Sanjuro (Toshiro Mifune) wanders into a village under the control of two rival factions. Sanjuro’s astute mercenary mind determines that escalating the fight between the two factions would be to his advantage. And the confident and self-assured Ronin enacts a complex plan to reach his goal.

In Yojimbo, the legendary Kurosawa strikes the right balance between drama, comedy, and tense action. In terms of tone and mood, this film was relatively light-hearted, particularly due to the ultra-cool screen presence of Mifune. The cunning and sassy Sanjuro is one of the most interesting anti-heroes in cinema. Sergio Leone took the scenario and character from Yojimbo to fit into his violent spaghetti Western A Fistful of Dollars (1964), starring Clint Eastwood.

3. Samurai Rebellion (1967)

Masaki Kobayashi’s Samurai Rebellion is set in 18th century Japan and follows Isaburo Sasahara (Toshiro Mifune), a loyal swordsman of a powerful daimyo (feudal warlord). The 250-plus years of Tokugawa Shogunate (1603-1858) is believed to have brought unity and order to Japan. While it was considered as a peaceful era, Kobayashi showcases how feudal systems are inherently violent and inhumane.

Isaburo is trapped in a loveless marriage for two decades with an upper-class woman. His eldest son Yogoro also seemed to be destined for a similar fate. Fortunately, Yogoro’s marriage is characterised by compassion and love. But the Sasahara family receives a shocking order from the Shogunate, leading to their inevitable rebellion.

Kobayashi is a masterful storyteller whose visuals are crafted with painterly precision. Isaburo was one of the few great characters Mifune played outside of Kurosawa’s films. His fiery performance lays bare the hypocrisy of the ruling class.

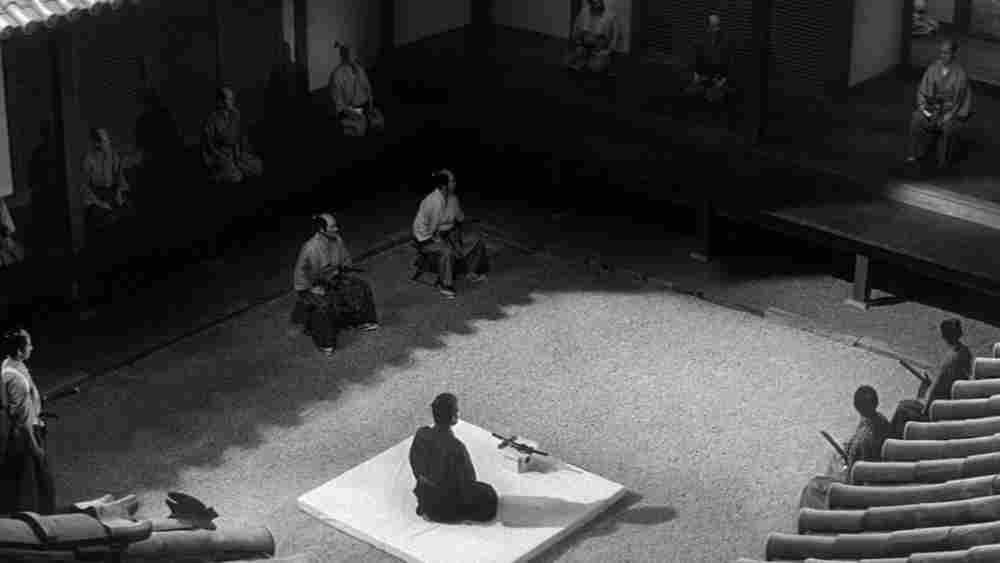

2. Harakiri (1962)

Masaki Kobayashi was one of the most important post-war Japanese filmmakers. He made the humanist, anti-war masterpiece Human Condition Trilogy (1959-1961). But his career-best work was the dark samurai drama Harakiri. The narrative takes place in the earlier half of 17th century Japan when different factions of feudal era Japan came under the control of the Shogunate – a hereditary military dictatorship. (you might want to put this description at the top where you first mention the word – Shogunate) Samurai who strictly adhered to the Bushido code (moral code of conduct for Japan’s warrior class) found it hard to survive during this relatively peaceful time.

Harakiri follows one such impoverished masterless samurai named Hanshiro Tsugumo (the great Tatsuya Nakadai). He demands an audience with his local lord in order to commit the ritual suicide, known as ‘Harakiri’. But before committing the act, Hanshiro narrates a chilling story. Kobayashi’s stark samurai epic offers a brilliant indictment of the Japanese militarist society. He demonstrates how governments consistently employ codes of honor to control people and create rigid social structures.

1. Seven Samurai (1954)

Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai is not only the best samurai movie, but also one of the greatest films of all time. No superlatives can quite adequately describe this epic. The 3.5-hour-long black-and-white action drama is set in 16th-century Japan, an era of civil war, social upheaval, and starvation. When the inhabitants of a village are threatened by bandits, they hire a band of ronin – masterless or unemployed samurai – to protect their livelihood. It’s primarily a good versus evil narrative that was amplified by the most revolutionary visual storytelling.

Apart from the brilliantly choreographed action set-pieces, Seven Samurai also intimately explores the social and political problems of feudal Japan. At the same time, the film carries a universal emotional appeal. Kurosawa’s samurai epic was clearly inspired by Western genre cinema. But his mastery of the visual language in Seven Samurai inspired countless films in world cinema.

Conclusion

There we are! These are some of the best samurai films of all time. Akira Kurosawa is an unparalleled master when it comes to samurai cinema. However, listing each one of his greatest samurai movies wouldn’t leave enough room on this short list for other deserving works from the same subgenre. Rashomon (1950), The Hidden Fortress(1958), Kagemusha (1980), and Ran (1985) are other must-see Kurosawa samurai-era tales.

If you’d like to explore the samurai genre beyond Kurosawa, here are some more titles. Orochi (1925), Samurai Saga (1959), Sword of the Beast (1965), Samurai Spy (1965), Goyokin (1969), Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo (1970), Gonza the Spearman(1986), Gohatto (1999), When the Last Sword is Drawn (2002), Blade of the Immortal (2017), Killing (2018).

And for all you Kurosawa fans, here’s our ranking of his greatest films: